DISABLED WOMAN

The Forging of a Proud Identity

By Nadina LaSpina

Keynote delivered on October 2, 1998 at

Southern Connecticut State University

Women's Studies Conference "Fulfilling

Possibilities: Women and Girls with Disabilities"

RIPOSTO

In Riposto, the little town in Sicily where I was born and lived till

I was 13, every girl learned, at a very early age, what her destiny as

a woman would be. Destino. That was the word used in Sicily, when

I was growing up in the 50's. Every little girl learned that "a woman's

destiny" was to get married and have children. Unless, of course, she was

too ugly to find a man that would marry her, then she could became a nun,

or, horror of horrors, end up a zitella - an old maid.

At a very early age, I learned that getting married and having children

was not my destiny. The message came across to me quite clear though

never loud -- it came in hushed tones and sighs and sorrowful looks. I

would not grow up to be like other women because I was not like other girls

-- I was a crippled girl. Ciunca, that's the Sicilian word for crippled.

Oh, I was a pretty little girl. But I knew beauty was wasted on me.

When I was 4 or 5, I started insisting that I was brutta, ugly.

I would get very angry when anyone said I was pretty. "Oh, che bella

bambina! Such a pretty little girl! Che peccato!, What a sin,

what a shame!" There would be such sorrow in their voice, such an anguished

look on their face... And I would look at my mother, who was carrying me,

and, even if she had been laughing a minute before, suddenly her eyes would

fill with tears and her face would turn into a mask of agony and shame.

She looked like the Addolorata. The Addolorata (the word

means "grieving" "sorrowful") was a statue in the convent across the street

from where we lived of Mary holding the dead Christ. It was a Sicilian

version of Michelangelo's Pieta: the mother dressed in black and purple

silk, sorrow carved deeply into her painted face. I didn't want my being

pretty to make people sad. So I wanted to be ugly. If I were ugly, at least

I could grow up to be an old maid or a nun.

I never did understand why the other girls thought old maids were so

horrible. The one old maid I knew, a distant cousin of my maternal grandmother,

was rather nice and I didn't even think she was that ugly. But whenever

she came over, it was to ask for money. "Why doesn't she have any money?"

I would ask my mother. "Because she has no husband," was always the answer.

I certainly didn't think being a nun was so bad. At the convent of the

Addolorata there was an elementary school. Right after I turned

five, I started first grade there. My mother used to carry me across the

street and hand me over to the nuns who would carry me to the classroom,

and carry me to the chapel and out to the garden and even into the kitchen.

I was passed around from one nun to another. They all smelled so good,

of incense and food and flowers. They spoke of Christ as their spouse.

I thought it would be nice to live at the convent. But I was afraid that

Christ would not want me as a his spouse. All the nuns could walk, none

of them were crippled like me.

Connie Panzarino, growing up Disabled at the same time but in NY, did

ask her catechism teacher: "When I grow up, can I become a nun like you?

-- No darling. I'm afraid that to be a nun and to serve God you have to

be able to walk and take care of yourself," was the answer. "Even God was

rejecting me," Connie writes in The Me In the Mirror.(1)

I know just how she felt.

When I first read Connie's book I was surprised to learn how very similar

our childhood experiences had been though we grew up in different continents.

I especially identified with her total dependence on her mother: "It always

seemed like I belonged to my mother. Since she took total care of me, she

had total power over me . . ." "It was hard to know if I could ever exist

separate from her..."(2) Connie's words

could be my own.

Unlike Connie's mother, who would at times become impatient and even

hit her, my mother did not allow herself to get angry. She was resigned

to her destiny. She knew she had to atone for the sin of having a crippled

daughter. She accepted her suffering like a good woman. You see, in Sicily,

all women suffered. They believed that a woman's destiny was to suffer,

atone for the sin of being a woman. I remember sitting on my mother's lap

listening to the Sicilian women talking about their sufferings: the curse

of menstruation, the toil of pregnancy and childbirth, the ravages to the

body caused by pregnancy after pregnancy... and they suffered the exhaustion

of raising children, the rigors of poverty... and many of them suffered

their husbands - their brutishness, maybe their beatings. My mother, carrying

in addition the cross of a crippled child, was the epitome of suffering

womanhood. She was the living Addolorata.

The nuns did their best to instill in me the sense of guilt and of shame,

and to teach me to embrace my own destiny of suffering. One day, when Sister

Angelica started with her "Offer your suffering to the Lord "routine, I

rebelled: "But I want to be happy!" I blurted out. She started stroking

me and kissing me: "Oh, my poor darling, how could you be happy? You can

never be happy!" I don't know were the anger came from. "I can be

happy," I cried and I struggled to free myself from the nun's ominous embrace.

But how could I expect to be happy when I really had no idea what would

become of me. If I couldn't get married and have children like other women,

what could I do? I didn't know any women who worked outside of their home.

I had heard that unmarried women found work cleaning rich people's houses.

But I knew I'd never be strong enough for that. My mother, who was an expert

with needle and thread, told me women could make money as seamstresses.

She tried to teach me to sew. But I hated it. I would stick my finger with

the needle on purpose and cry.

When I was in third grade, a young woman came to work as a teacher at

the convent. I was really surprised because I thought only nuns could be

teachers. She had long hair which she wore in a pony tail. I fell madly

in love with her and decided I would not let my mother cut my hair anymore,

and that I would be a teacher. My heart was broken when she didn't come

back to teach at the convent the next year. I found out she had gotten

married. So I let my mother cut my hair short again and I called myself

stupid for believing I could be a teacher when I couldn't walk.

In school I was a model student, the nuns' pride and joy. My progress

seemed to make my father very happy. He always encouraged me to study --

which was a bit strange since other girls's fathers didn't really care

how their daughters did in school. Their sons were a different story. Was

my father thinking that I 'd better use my brain since my body was no good?

Did he believe back then that using my brain could get me anywhere - in

Sicily?

But my father had a plan: he would take me to America where I would

walk, where I would be cured. My father was a gentle, generous, funny man.

My mother was always at a loss when the other women exchanged stories about

their brutish husbands. I adored my father. To me he was the smartest,

the handsomest, the greatest man in the world. I always believed everything

he said. He had taken me to Catania, to Messina and to Rome, to the best

hospitals, to the best doctors, in the quest for a cure. But his dream

was America. He was sure the doctors there would know what to do to cure

me.

Doctors scared me because they always hurt me. I preferred being taken

by the women (by my grandmother, my aunts, my mother) to the healers, and

to the witches. Oh, I liked the witches! They scared me, but it was an

exciting kind of scared. I knew they would never hurt me like the doctors

did. Of course, I never thought they could make me walk, but I did believe

they could teach me how to fly. Everyone in Sicily had seen the witches

flying in a circle holding on to each other's hands in the dark of night.

To me it sounded like such a wonderful game, even better than girotondo

(ring around the rosie), the game little girls liked and little boys snubbed.

I played girotondo. I would sit in the middle of the circle &

watch the other girls go around me.

All the talk about cure just confirmed for me what I already knew: that

there was something terribly, horribly wrong with me. I just could not

remain the way I was, ciunca. I was just no good that way. Nobody

wanted me to be the way I was. The only way for me to have a life was to

be cured. And since they couldn't cure me in Catania and Messina and Rome,

I had to go to America. But what if we never made it to America? What if

I never got cured?

Sometimes I thought that if I could just sit someplace, if I didn't

have to be taken anywhere, if I never had to go to the bathroom, maybe

people would not notice that I was crippled.

There must have been Disabled people living in the town, but I never

saw them. I had heard people referring to the shoemaker as "cripple."

I didn't understand why, maybe he had a limp. The town beggar was called

"cripple," and also "dumb" "babbu." He walked and talked funny --

he probably had CP.

I didn't know any Disabled women and I didn't know any other Disabled

kids. My mother once told me that there was a crippled girl just like me

who lived in an another town. Maybe she made her up so I wouldn't feel

that I was the only crippled girl in the world. I thought about that other

little girl as a lost sister and often fantasized about meeting her and

playing girotondo with her.

(That's from my memoir. Well, every crip is writing a memoir these days,

so why not me?)

ROLESSNESS OF DISABLED WOMAN

My experiences growing up in a little town in Sicily were probably more

extreme than those of Disabled girls growing up in the US, but I know they

were not unique. Riposto. That's where I'm coming from. That's

where I started out. But didn't we all start out back there? Don't

we all recognize that place, that time? We thought we were the only ones,

we felt we were to blame, we didn't know what would become of us. And I'm

not talking only about those of us who grew up Disabled, but also those

who acquired a disability later, as adults, and discovered that everybody

suddenly seemed to be writing off their life. Because our history has been

covered up and never been recorded, because our people have been hidden

away and silenced, it is common when we find ourselves in disability land

to feel isolated, to think we are the only inhabitants. In a world where

disability is intolerable and the consent is that it must be eradicated,

in a world where different means inferior, where do we fit in? How can

we fit in? If we cannot be cured, can we at least be as inconspicuous as

possible, can we try to cause as little trouble as possible, can we try

to look and act as "normal" as possible, can we at least make the world

tolerate us? The future can seem a desolate wasteland.

That's true for all of us: Disabled women and Disabled men. But for

Disabled women, oppressed by sexism as well as by ableism, that wasteland

can be even more desolate. In 1981, Adrienne Asch and Michelle Fine wrote

their groundbreaking paper "Disabled Women: Sexism without the Pedestal."

Since then we've been talking of Disabled women as "roleless." Not seen

as fit to fill economically productive roles because we're women, we are,

because we're Disabled, shut out of the traditional roles of wife, mother,

homemaker, nurturer, or lover, and deprived even of women's double-edged

status of "sex object on the pedestal."(3)

Carol Gill sees the de-sexualization of the Disabled woman as eugenic

in intent. "Keeping us genderless by discounting us as women and as sexual

beings helps to prevent us from reproducing, which keeps us harmless to

society."(4) Barbara Waxman Fiduccia agrees:

"I believe this is done tacitly to keep us from doing the thing that poses

an overwhelming threat to our disability-phobic society: marrying their

sons, bearing their grandchildren."(5) Barbara

Waxman has been rousing us -- Disabled men as well as Disabled women --

to fight our sexual oppression for many years. "Why hasn't our movement

politicized our sexual oppression as we do transportation and attendant

services?" she asked in 1991.(6)

Barbara Waxman and Marsha Saxton together have written a Disability

Feminism Manifesto. "Mainstream feminists have battled limited gender

roles for nondisabled women: sex object, wife and mother. But as Disabled

women, we've had the opposite problem: We've been denied sexual, spousal

or maternal roles when we wanted them." So, first of all, they proclaim,

"We want our sexuality accepted -- and supported with accurate information."(7)

Indeed, Disabled women have been fighting for the right to be attractive

and sexual, at times acting in ways that would make our feminist sisters

frown. I remember that as a feminist I was appalled when Ellen Stohl (a

gorgeous quadriplegic woman) posed for Playboy. But as a Disabled woman,

I understood and fully identified with her need to flaunt her sexiness.

Recently, in a Disabled women's group, a few of us started talking, with

some embarrassment but with a great deal of gusto, about having been in

our younger days "nymphomaniacs" (those were the days before AIDS).

Because we are not seen as "real women with real women's bodies," Waxman

and Saxton remind us, we are denied access to information on reproductive

issues and often to reproductive health care. Many of us are not offered

birth control, while others are forced to use birth control and even sterilized

against their will (certainly true for our sisters with mental retardation).

Because inaccessible exam tables and mammography machines make it difficult

for many of us to go for routine screening, and because, I will add, physicians

are less likely to investigate signs of serious conditions, such as cancer,

when the woman has a disability, our very lives are at risk. Disability

Feminists say: "We want equal access to reproductive health care."(8)

The Disability Feminism Manifesto also calls for the elimination

of disincentives to marriage which are built into programs such as SSI

and Medicaid. And it proclaims the right of Disabled women to have children.

"We want more resources for mothers with disabilities to care for their

own children and to have access to adoption."(9)

Because abortion is either not available or is forced upon a Disabled

woman because it is assumed she cannot be a good parent, disability feminists

say: "We want uncoerced choice."(10)

Lastly, because nondisabled women are routinely pressured to use prenatal

tests to find out if their unborn baby has a genetic condition and then

pressured to abort if the test shows the presence of a disability, Waxman

and Saxton say: "We want all women to understand that they can refuse

to have these tests [and refuse to have an abortion]. We want children

with disabilities to feel welcome in the world."(11)

There is no question that selective abortion is eugenic in intent. We

have good reasons to worry about being "selected out." Attempts to do away

with our kind run like a thread through human history, from Greco/Roman

times when Disabled infants where exposed to the elements, to Nazi Germany's

euthanasia program, which saw the systematic extermination of at least

200,000 Disabled people. We are always at risk of new ideas which allow

old prejudices to strut around in the clothing of compassion, of new and

desirable social advances. There can be no question that such practices

as the selective abortion of Disabled fetuses, and the non-treatment of

Disabled infants, as well as the rationing of health care, the coercion

of Disabled people into signing DNR's, and (today's hot button issue) physician

assisted suicide, all have as a goal the extinction of the Disabled population.(12)

VIOLENCE AND ABUSE

We should include in the Disability Feminism Manifesto that "Disabled

women want to live free from violence and abuse." Violence and abuse

issues were rated the number one priority by women with disabilities in

a national survey (conducted by Berkeley Planning Associates) in 1996.

Studies overwhelmingly show that we are more at risk of abuse (2 or 3 times

more).(13) That's not surprising, when

we add to all the issues of control and power brought up in Corbett O'Toole's

very powerful film (shown at the Conference), the hatred of disability,

so pervasive in our society. As Disabled women we are more likely to tolerate

violence and abuse. We have been taught to hate our disabled bodies, so,

at some level, we may feel our bodies deserve to be hurt. We have been

told we are not attractive and sexual, so we should be "grateful" for any

attention we get.

Disabled women have spoken out about a rarely identified form of abuse:

being forced to disrobe and pose for display and photos in medical education

settings, usually before mostly male audiences of doctors & medical

students. It was certainly most traumatic for me, 13 year old, coming from

a place where modesty was valued as a woman's supreme virtue, to have to

strip naked in front of a room full of men.

In discussing such experiences with my friend Hope DeRogatis, we both

recalled that, not only we did not complain, we did not mention anything

to anyone including our parents. Hope remembered forbidding her parents

from going into the examination room with her. She couldn't bear to have

her parents witness her humiliation and, at a certain level, her guilt.

It was a dirty secret. We reacted to this violation the way many girls

and women react to sexual abuse and rape.

Disabled women may also put up with abuse because we often feel that

our bodies do not belong to us. We are forced to get used to strangers

touching us, handling us, manipulating us, inflicting pain on us. Many

medical procedures and treatments are undoubtedly forms of violence and

abuse and torture. I was in and out of hospitals for ten years, had surgery

13 times. I was a good patient, never complained. I know I felt an obligation

to my father who uprooted the family so I could to be cured. Maybe I thought

I had to atone for the sin of being a crippled girl, accept my destiny

of suffering, like my mother, like the good women of Sicily. In those hospitals,

I put up with waking up suddenly in the middle of the night because I felt

a man's hand on my breast, or with having a penis pushed in my face while

being pushed down to therapy, the same way as I put up with the surgeons'

scalpels, and the body casts, the braces, the learning to walk, the falling

& breaking of knees and ankles... till my polio legs were wrecked beyond

repair and had to be amputated at the knees.

BEING WITH OTHER DISABLED KIDS

But there were happy times in those hospitals. It was in the hospitals

that I came into contact for the first time with other Disabled kids. The

very first hospital I was in was the Hospital for Special Surgery in NY.

I was on a floor of children and teens. All had disabilities. I couldn't

speak a word of English, but I started making friends rights away. I was

elated. In Sicily I had thought I was the only crippled girl in the world,

and here were all these other Disabled girls and boys. There was a beautiful

girl my age named Wendy who had spina bifida. I had dark hair, she had

blond hair. I had brown eyes, she had blue eyes. We became best friends.

Cheryl Marie Wade recalls: "When I was a teenager becoming a Cripple,

the happiest times I had were those spent in a children's convalescent

home ... where I lived with other teenagers becoming Cripples. To them

I was not the other. It was here a seed got planted in me that I was connected

to a group, and that as a group we had things in common that belonged to

us."(14)

Judy Heumann also speaks of being with other Disabled kids as a very

necessary step in identity formation and as a first step in her politicization.

"...we talked to each other about situations such as, "What would you do

if you were going down the street and somebody started staring at you?"

We decided that we would turn around and say, "Take a picture, it lasts

longer." I remember the first time we said this to somebody... we were

laughing so hard. It was school experiences like these that made me realize

that together with other Disabled people we could assume power."(15)

WENDY

Finally out of hospitals, and starting college, I went through a time

when I tried my best to fit in the nondisabled world. As all young people,

I wanted to be accepted, I wanted to be liked. I never really tried to

"pass." I didn't go out of my way to avoid other Disabled people. But as

I tried to make nondisabled friends, I lost contact with the friends I

had made in various hospitals and convalescent homes. But not with Wendy.

Through the years Wendy and I continued to see each other as often as we

could (which wasn't very often since I lived in Brooklyn and she lived

in Long Island and we had to rely on somebody to drive us). But we talked

on the phone almost every day. Then my parents moved to Queens which was

a bit closer to Long Island, and Wendy got a car.

I remember she would pick me up and we would go riding around. Seeing

us in the car, no one could tell we were "handicapped" (that was the word

that was used then). We were two hot chicks, a blonde and a brunette, out

joy riding. Guys on the street would whistle when we stopped at a light,

from other cars some men blew us kisses, some made lewd remarks. You know

-- the kind of behavior women in the CR groups of the late 60's were calling

offensive and demeaning, even labeling it sexual harassment. We soaked

in every lustful look. We savored every obscene word. I did feel a bit

uncomfortable since I was starting to pay attention to the Women's Liberation

Movement. But I loved riding in Wendy's car. I thought we were having fun.

But Wendy was doing it to torture herself. "All I have to do is park, get

the chair out and they'll run the other way so fast!" she would say. "We're

both beautiful, we could have it all, why do we have to be handicapped?

I don't want to live as a handicapped woman. I want to be a real woman,

I want a real life, I want happiness. If I can't have all that, I'd rather

die."

I couldn't tell her "We are real women, we can have a

real life, we can be happy." I didn't have the words yet. I couldn't

tell her that it was our "internalized oppression" that made her hate her

disability and hate herself. I couldn't tell her that what made her so

unhappy was not her disability but the way society treated her because

of it. "The social model" of disability had not been formulated yet. The

view of "disability as a personal tragedy" still reigned supreme. We didn't

have the weapons to fight the "better off dead" attitude. Wendy swallowed

that lethal lie --hook, line & sinker.

And yet the women's movement was already telling us that "biology is

not destiny." Why didn't I grab a hold of those words, why didn't

I use those words to save Wendy?

I quietly witnessed Wendy's despair. I felt as if I was back in Riposto.

The forces of doom closing in on both of us, crippled girls. "This is your

destiny." I could see the Addolorata beckoning me. I could hear

again sister Angelica's ominous words "You can never be happy."

We were both 22 when Wendy drove to a Long Island motel, checked herself

in, locked the door and swallowed 60 seconals.

It was 1970. That same year in New York Judy Heumann would sue the Board

of Ed. and found Disabled in Action. In Berkely, Ed Roberts would soon

open CIL, the first Independent Living Center. The Disability Rights Movement

would soon start to bloom. I still think that if Wendy had held on a little

bit longer she would not have had to kill herself.

I didn't think I could ever climb out of the deep depression Wendy's

suicide threw me in. But I did. And I threw myself into the new movement,

and I saved my life.

COMING HOME

"Coming home" -- that's what Disabled people call the experience of

connecting with the disability community. Cheryl Marie Wade calls it a

miracle. We "come home" after a period of isolation. Some of us may just

not have had the chance to meet other disabled people. Others might have

been avoiding other disabled people, trying to fit in the nondisabled world,

"passing" -- at great cost. Leslie Heller, who passed for many years, told

me (in a recent conversation): "I had to suppress such a big part of myself

in an attempt to be accepted into a world that would not accept me anyway.

I was left feeling nonexistent."

"Coming home" can happen at a disability related event, suddenly finding

oneself in the presence of many Disabled people -- For Anne Finger it was

a post-polio conference: "It was as if I'd been living all my life in a

foreign land, speaking a language that was not my native tongue," she writes

in Past Due.(16) Or you can feel

connected just by meeting one person -- Kate, the protagonist of Jean Stewart's

novel, The Body's Memory, feels "she has come home" when she meets

Sheba, the 'respirator woman' who introduces Kate to the disability rights

movement.(17) Today Disabled people connect

on the internet. Many of the students in my online disability culture course

say they take the course because they need to "come home." One of the most

powerful ways of connecting is finding each other shoulder to shoulder

in a disability rights action. None of us in the movement will ever forget

our first demonstration, our first arrest.

IDENTIFYING WITH OUR SISTERS

Of course, Disabled men experience "coming home" -- Irv Zola's Missing

Pieces is a classic account of "coming home." But for Disabled women

"coming home," goes beyond joining the community. We try to find ourselves

in our sisters, to see other women as reflections of ourselves. Leslie

Heller in her article "I am the Other" talks about the women in her Disabled

women's group: "With them as mirrors, I began to entertain the possibility

that my value, like theirs, is not diminished by disability."(18)

In "A Different Reflection," Hope DeRogatis speaks of Ona, her first Disabled

friend: "I could watch her as I could not watch myself... Her strength

and loveliness were undiminished by a different body, I could see my own

beauty because I could see hers."(19)

Kate, in Jean Stewart's novel, says other Disabled women "served as

beacons" for her. "My presence , my personal way of being in the world,

underwent a sea change." Jean writes, "It had to do with how they held

their heads. How some women in manual chairs jumped curbs, practical, preoccupied

with getting from here to there... How they entered rooms full of nondisabled

people, as if they had a right. How, breathing into fat-ribbed respirator

tubes, certain quadriplegic women paused to smile. How respirator breathing

could seem suddenly sexy in a way that dragging on Virginia Slims never

would..."(20)

Oh yes, I remember when, after years of comparing myself to nondisabled,

skinny, longlegged models in magazines, after years of looking at my naked

body in the mirror only from the waist up, after years of trying to compensate

for what I thought I was lacking, I started really looking at Disabled

women and started noticing how beautiful and strong and powerful and sexy

they were. And I started telling myself that's how I want to be, that's

who I want to be.

WOMEN TALKING

Women know how important it is to "talk." We Disabled women do a lot

of talking. We talk one to one, and we form Disabled women's groups, following

the tradition of the women's movement groups of the late sixties and early

seventies. Because we know how much we need each other. Because we know

the value of that feminist adage "the personal is political." Hope DeRogatis,

talking about making friends with Ona, says: "We were overflowing with

things to say to each other, laughing with each other... interrupting each

other with stories and thoughts that were the same. We finished each other's

sentences - words neither of us had ever spoken out loud before."(21)

Feminist film maker, Bonnie Klein, who became Disabled after a stroke,

writes about connecting with DAWN, the Disabled Women's Network in Canada:

"It is like the early days of consciousness-raising in the women's movement:

sharing painful (and funny) experiences, "clicks" of recognition; swapping

tips for coping with social service bureaucracies and choosing the least

uncomfortable tampons for prolonged sitting. It is exhilarating to cry

and laugh with other women again. Here I am not other, because everyone

is other. It is the sisterhood of disability."(22)

PERSONAL EXPERIENCE / THE BODY

Disabled British feminist Jenny Morris believes a feminist perspective

can do a lot for the disability rights movement. "In our attempts to challenge

the 'medical' and the 'personal tragedy' models of disability, we have

sometimes tended to deny the personal experience of disability." "While

environmental barriers and social attitudes are a crucial part of our experience

of disability... to suggest that this is all there is to it is to deny

the personal experience of physical or intellectual restrictions, of illness,

of fear of dying."(23) Cheryl Marie Wade,

in her inimitable style, recalls how "Even socially, when it was just us

crips together, we never talked about our bodies, our disabilities, our

physical realities; we talked political action. I started feeling more

and more out of sync with the disability is a social construct point of

view... I was pissed as hell that no matter how many political speeches

I made, my body kept calling the shots."(24)

I remember how pissed I was, years ago, when my post-polio symptoms

really hit me. "What is this? I'm supposed to be the 'able Disabled,' I'm

supposed to be 'Disabled not sick!' Can't I figure out a way to blame this

pain on society? Who can I demonstrate against?"

Not all bodily suffering is a socially curable phenomenon. Some physical

pain is simply the consequence of having a body that's made of flesh. All

living creatures know pain. Those of us living with disabilities may know

more than most. I'm beginning to think the Sicilian women had a point when

they talked about a woman's destiny of suffering: this menopause business

sure is no fun.

While writing this keynote, I was reminded of how not only my physical

energy but my mental energy has decreased with the years. I used to be

able to write all day (and all night if necessary). Now I write in spurts.

Hoping ginseng or ginkoba might help, I went into a health food store.

It was a Saturday and the place was packed. As I tried to make my way through

the aisles, I kept looking at all those bodies. They were all so fit! So

perfect! In spite of myself, I started admiring these people who took such

good care of themselves. And then I started looking at the expressions

on their faces as they picked up and very carefully inspected bottle after

bottle. And then I heard the quiver in their voices as they asked question

after question of the equally perfect looking salespeople. I recognized

the emotion that enveloped them: it was fear. They all lived in fear of

losing their perfect proportions, their precious health. I really felt

sorry for them, and grateful for this crippled body.

This 50 year old Disabled woman's body, that has known so much pain,

struggle and joy.

Again using a feminist perspective, Disabled women have in recent years

set out to reclaim the female Disabled body. It was looking at Frida Kahlo's

paintings that made Cheryl Marie Wade realize the full value and beauty

of our "damaged and powerful, ravaged and exquisite" bodies: "The vividness

of her pain, her lush, sensual femaleness. You deny my pain and struggle,

then you deny my beauty and grace."(25)

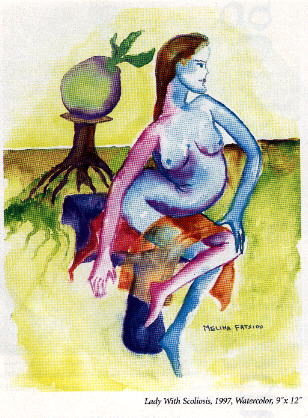

Disabled artists today are writing, painting, performing the Disabled

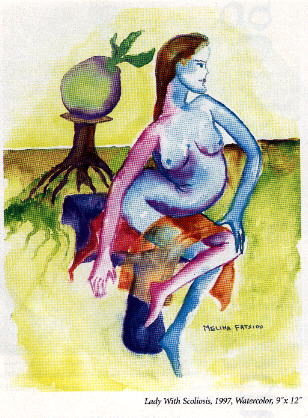

woman's body. Melina Fatsiou-Cowan paints magnificently swirling female

bodies with scoliosis. "I used to hate, loathe my scoliosis... I was told

deformity was a repulsive thing... so I used to think that touching my

scoliosis would be as shocking ...as touching death itself," she says.(26)

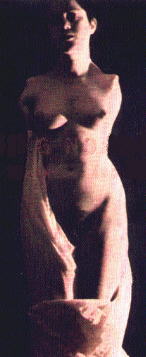

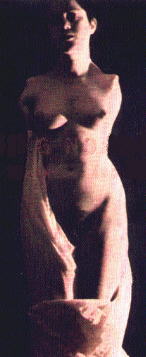

Mary Duffy, who was born without arms, makes of her own naked body a work

of art when she stands partially draped in white cloth, very much like

the Venus de Milo. "By confronting people with my naked body, with its

softness, its roundness and its threat, I wanted to take control... I wanted

to hold up a mirror to all those people who had stripped me bare previously...

the general public with naked stares, and more especially the medical profession."(27)

FEMINISM AND DISABILITY

Though many Disabled women embrace feminism, feminism has not welcomed

Disabled women. There have been and still are clashes because our positions

on certain issues are not understood. I've been thrown out of feminist

meetings for opposing selective abortion and, more recently, physician

assisted suicide. In order to throw me out of one meeting, years ago, they

had to carry me out since their meeting place was not accessible -- and

they had carried me in with such kindness and compassion...

The Disabled woman has traditionally been left out of feminist theory

and feminist analysis. We have felt that we were an embarrassment to feminists.

Bonnie Klein, attending a feminist film festival after her stroke, wrote:

"I feel as if my colleagues are ashamed of me because I am no longer the

image of strength, competence, and independence that feminists, including

myself, are so eager to project."(28) Adrienne

Asch and Michelle Fine wrote back in 1988: "Perceiving Disabled women as

childlike, helpless, and victimized, non-Disabled feminists have severed

them from the sisterhood in an effort to advance more powerful, competent,

and appealing female icons."(29)

Nondisabled feminists see Disabled women as reinforcing traditional

stereotypes of women. In reality, "disabled" in its most negative meaning

with all its bad connotations, has been used to define woman. Historically,

in male dominated cultures, 'woman' has been seen as lacking, as less than,

as "disabled." Aristotle propounded the notion of a hierarchy with men

at the top, of course, and women one step below -- a step which, in Aristotle's

words, represents "the first step along the road to deformity." (30)

Through the centuries this view of woman has thrived, culminating in the

work of Sigmund Freud. According to Freud a woman is a disabled man, a

castrated man, a "mutilated creature" destined to waste her life envying

what she doesn't have: that precious penis. Freud speaks of the woman's

lack of a penis as a wound "After a woman has become aware of the wound

to her narcissism, she develops a scar, a sense of inferiority."(31)

My favorite feminist, Kate Millet wrote in 1970 in Sexual Politics

"A philosophy which assumes that 'the demand for justice is a modification

of envy' and informs the dispossessed that the circumstances of their deprivation

are organic, therefore unalterable, is capable of condoning a great deal

of injustice. One can predict the advice such a philosophy would have in

store for other disadvantaged groups..."(32)

I wish I could say Kate Millet was thinking of Disabled people when

she wrote that, but I don't think she was. My nondisabled feminist friends

today still fail to make the connection. When they ask me to explain what

I mean when I say "I don't want to be cured," I always answer "The same

thing I mean when I say I don't want a penis." And the immediate response

is: "Oh, it's not the same thing! You really are disabled!" Yes, I really

am Disabled and I have no desire to be non-Disabled. Just like I really

am a woman and I have no desire to be a man.

But ableist thinking is just too pervasive. Even the people you really

think should, don't get it. Carol Gill says: "It really rocks people

when we so clearly reject the superiority of nondisability. We're attacking

the old yardstick of human validity--the reassuring bottom line: 'At least

I have my health (all fingers and toes, ability to walk, vision, mind...)'"(33)

People are just too afraid of becoming ill, of becoming Disabled, of dying.

They cannot believe that we do not 'envy' them what they value so dearly,

what they are so afraid to lose: their precious health, their able body.

Our most progressive nondisabled friends will support us when we fight

for our rights, when we demand access. But they just don't understand what

we mean when we say we don't want to be cured because we are "Disabled

and Proud."

PRIDE

When you're Disabled you're always being asked questions (what's wrong

with you? How did it happen? And how do you do this and how do you do that?),

always being asked to explain, to justify yourself. We 're all used to

it. If we're feeling cocky we may give a smart answer (What's wrong with

me? What's wrong with you?)

When they ask us "What do you mean by Disabled and Proud?" what they're

implying is that we don't have a right to be proud. "How can you be proud

when you're disabled?" It is an insulting question. Yet we feel

the obligation to explain. I sure have done a lot of explaining to journalists

who never hear a word I say, to colleagues at the New School who don't

have an inkling of what I'm doing there, to nondisabled old friends who

still don't know who I am, and to my own Disabled sisters and brothers

who are not quite there yet. It is always so difficult to explain

what we mean. I always blame the difficulty on my listeners, of course.

But I realize that the difficulty may be within us. We may not be so sure

ourselves that we have the right to be proud.

Bonnie Klein, at the Disability Pride Day Rally in Boston, started chanting

with the crowd "Disabled and Proud!" and then: "My throat jammed on the

word mid-chant." she writes "Is this honest? Who am I trying to fool? It's

one thing to accept but another to be proud. I'm proud of surviving and

adapting maybe, but am I proud of being Disabled?"(34)

Obviously not, not then, not yet.

Laura Hershey is as proud as they come. I have a button which says "you

get proud by practicing" which is the title of one of her poems. One of

her recent online "crip commentaries" (wonderful weekly articles posted

on her webpage), is titled "What's pride got to do with it." The commentary

answers a question asked by a passerby who noticed the sign she was wearing

at an anti-telethon protest this past Labor Day. Laura's sign said "Disabled

and Proud." The stranger's question, of course, was "What does that

mean?"

Laura's explanation is beautiful. "What does it mean to be "Disabled

and Proud"?" she writes, " For me, it means that while everyone else is

making their own unique contribution to the world, I'm making mine too.

It means I can be a lot of things -- a compound of identities, roles, experiences,

gains, losses, feelings, ideas, actions -- and that every piece of me belongs

together. None of my pieces need to be erased or hidden. And I'll fight

the idea -- whether promoted by Jerry Lewis, or by Jack Kevorkian -- that

disability is intolerable and must be eliminated from the world."(35)

Yet Laura finds it necessary to make this distinction. She's saying

"Disabled and Proud," she is not saying that she's "Proud to be

Disabled." "I'm not taking credit for the fact that I was born with a disability.

That was pure chance. Nor do I consider myself, or other people with disabilities,

better than nondisabled people," she writes.(36)

I probably have said similar things in the past. Why do we feel we have

to? Our gay brothers and sisters don't make such a distinction when they

talk of gay pride, nor do our Deaf brothers and sisters (who when it comes

to Pride have shown us the way!). They'll say they're Deaf and Proud and

they'll say they're proud to be Deaf. Of course, it was pure chance I got

polio. But do people who say they're proud to be American worry that it

was pure chance they were born in this country?

It's like we're embarrassed to say we're proud. For centuries our people

have been taught to be ashamed. Are we so well indoctrinated that now that

we're finally feeling proud, we're ashamed of our pride? I am going to

say it. I am Proud to be Disabled!

You may have noticed that I've been saying Disabled woman and Disabled

people rather than woman with a disability and people with disabilities.

I see nothing wrong with adjectives, nor with placing adjectives before

nouns. I say I am an Italian woman, -- or much better, I am a Sicilian

woman. Placing the adjective "Sicilian" in front of the noun "woman" does

not diminish me, unless the person who's talking is a northern separatist

who thinks Sicilians are the scum of the earth. Why should putting "Disabled"

in front of "woman" diminish me? Unless the person who's talking is an

ableist who thinks I should be ashamed of being who I am. If you look at

the written version of this paper you'll see that Disabled is capitalized,

just like Sicilian would be capitalized. (And just like Deaf is capitalized.)

I realize that I say I'm proud to be Disabled the same way I would say

I'm proud to be Sicilian. So I guess I'm being 'nationalistic!' I'm

proud to belong to disability nation. Even though there is no geographical

spot on the map that we can call our "homeland," so we borrow from the

lesbian and gay movement and say: "we are everywhere." But:

"If there was a country called Disabled,

I would be from there. I'd live Disabled

culture, eat Disabled food, make Disabled

love, cry Disabled tears, climb Disabled

mountains and tell Disabled stories.

If there was a country called Disabled

I would say she has immigrants that come

to her from as far back as time remembers

If there was a country called Disabled, then

I am one of its citizens."(37)

A man wrote that poem. Neil Marcus. We have proud men too in this Disability

nation. The man in my life is "Disabled and Proud."

So go ahead, call me nationalistic, tell me I'm practicing divisive

politics, but don't tell me that my pride doesn't make sense. Really, why

is it that when some jerk says "I'm proud to be an American" nobody asks

him to explain what he means? Maybe we should.

It is only because this is America that people think you can only be

proud of your country if your country is rich and powerful (and imperialistic

and militaristic...) People who live in poor countries, or in countries

torn by war, where everyday is a struggle to survive, can be proud too,

and they can love their land in a way Americans will never understand.

I love the land of Sicily where I was born. It's a tough land. It sure

was tough for a crippled girl to grow up in Riposto. Yet I'm proud to come

from there.

It is only because this is America that people think you can only be

proud if you have a job that pays a lot of money, and you live in a big

house and drive a cadillac. Elsewhere in the world people know that it

is in struggle that you learn pride.

I am proud to be Disabled. I am proud that we are a people that has

endured centuries of oppression -- isolation, poverty, incarceration. That

has survived constant attempts to do away with our kind -- from the ancient

Greeks to Kavorkian. That in the last 30 years has fought a 'brave,' even

'heroic' battle for equal rights and managed to make some remarkable changes

in this world. Though our community is more diverse than any other on earth,

we come together so easily, so joyfully. In spite of the indoctrination

we all received to hate our disabilities and hate ourselves and each other,

today we love ourselves, and we love each other. Today our community is

flourishing, even though the struggle is far from over and most of us are

still poor and discriminated against, and many of us are still incarcerated

in nursing homes. Our people are giving voice to the disability experience,

telling their stories... our people are writing books, making films, creating

beautiful poetry, creating beautiful art... We are building culture --

Disability Culture.

So, don't we have every right to be proud?

And because we are Disabled women, we have to break free of double chains.

We have to struggle twice as hard to survive. So, because we are Disabled

women, our pride is even stronger. And our joy is greater when we come

together ( as we're doing at this conference) to learn from each other,

to show each other the way, to share each other's strength, to delight

in each other's beauty.

Do you mind if I do something?

Sister Angelica, I am happy!

And I am proud, Proud to be a Disabled Woman.

NOTES

1. Connie Panzarino, The Me in the Mirror

(Seattle: Seal Press, 1994), 53.

2. Ibid., 51.

3. Michelle Fine and Adrienne Asch, "Disabled women:

Sexism without the pedestal," Journal of Sociology and Social

Welfare, 8(2), July 1981, 233-248.

4. Carol Gill, "Cultivating Common Ground," Health/PAC

Bulletin, Winter 1992, 35.

5. Barbara Waxman, "Up against Eugenics: Disabled

Women's Challenge to Receive Reproductive Health Services," Sexuality

and Disability, 1993.

6. Barbara Waxman, "It's time to politicize our sexual

oppression," Disability Rag, 1991

7. Barbara Waxman and Marcia Saxton, "Disability

Feminism: A Manifesto," New Mobility, Oct. 1997, 60.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid, 61.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. See Lisa Blumberg, "Bad Baby Blues," The

Ragged Edge, July/August 1998

13. See Corbett O'Toole, "Violence and sexual assault

plague many disabled women." New Directions for Women, January/February,

1990.

14. Cheryl Marie Wade, "Identity," The Disability

Rag, Sept./Oct. 1994, 33

15. Judy Heumann, "Growing up, Creating a Movement

Together," in Diane Dredger and Susan Gray, Imprinting our Image: An

international Anthology by Women with Disabilities (Charlottetown,

Canada: Gynergy Books, 1992), 193.

16. Anne Finger, Past Due: A Story of Disability,

Pregnancy and Birth (Seattle: The Seal Press, 1990), 16.

17. Jean Stewart, The Body's Memory (New

York: St. Martin's Press, 1989), 237.

18. Leslie Heller, "I am the Other," Special

Edition, 1996, 2.

19. Hope DeRogatis, "A Different Reflection," Nursing

Outlook, Sep.93, 33.

20. Stewart, 237.

21. DeRogatis, 35.

22. Bonnie Klein, "We Are Who You Are: Feminism

and Disability" Ms., Nov/Dec 1992, 73.

23. Jenny Morris, From Prejudice to Pride

(London: Women's Press, 1990), 181.

24. Wade, 35.

25. Ibid.

26. Personal letter from the artist.

27. Quoted in Lennard Davis, Enforcing Normalcy

(New York: Verso, 1995), 149.

28. Klein, 72.

29. Adrienne Asch and Michelle Fine, Women with

Disabilities: Essays in Psychology, Culture and Politics (Philadelphia:

Temple University Press, 1988), 4.

30. Robert Garland, The Eye of the Beholder:

Deformity and Disability in the Graeco-Roman World. 1995

31. Sigmund Freud, Some Psychological Consequences

of the Anatomical Distinctions Between the Sexes

32. Kate Millet, Sexual Politics (New York:

Doubleday, 1970), p. 187

33. Carol Gill, "Disability Culture," Disability

Rag, Sept./Oct. 1995

34. Klein, 73.

35. Laura Hersheys's wonderful "crip commentaries"

are at the following web address: http://ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/LauraHershey

36. Ibid.

37. From Neil Marcus' play, Storm Reading.

Personal

Website of Nadina LaSpina

Go back to Course Page